Can’t We Just Hug Each Other?

I recently met an old friend for lunch. He’s known me since before I owned a flip phone. He was one of the first people I told I had a problem and was quitting drinking years ago.

As we approached each other outside the diner, I extended my hand for him to shake while he opened his arms for an embrace. There was an awkward pause before we quickly changed tactics: he reached for my hand, and I leaned in for a hug. We laughed nervously and settled on a fist bump, the weakest form of greeting between men our society allows. It’s been bugging me ever since.

The reasons dudes do what dudes do are sometimes lost to legend. But the answers are always simple. I didn’t hug him at first because I was momentarily transfixed by a parade of insecurities.

That moment of will-they-won’t-they slapstick between my friend and me led to a long, warm conversation over burgers about family, careers and growing older. Afterward, in the cold air, we said our goodbyes and hugged, both of us making sure to slap each other on the back a few times as if we were covered in spiders.

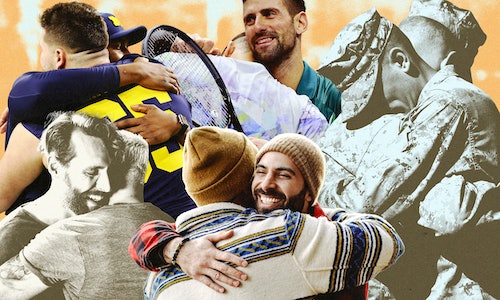

I’ve realized that there are three kinds of hugs between men: “The Mobster,” a modified version of the “You’re Covered In Spiders” hug. It is brief but energetic, and there’s lots of patting and mutual frisking. It’s not required, but you can say things like “ay” and “sup” and “my man” while performing this hug. Then there’s “The Sasquatch,” in which two dudes squeeze each other with love — they just crash into each other’s wide-open gorilla arms and squash it out. And finally, “The Brother,” a.k.a. the kind of hug two people who genuinely love each other give — long, close, you can feel their heartbeat.

As my old friend walked away, I wondered why I didn’t hug him at first. Why did I try to shake his hand? I once shook the hand of a colleague of my dad, a massive Texan bulldozer who was 50% belt buckle, 50% cigar. I was probably 10 or 11 and he looked as old as the Alamo. He sized me up and pumped my arm as if oil was going to gush out of my mouth. What I remember was how quick and aggressive he was, as if I, a little boy, was a threat.

Why, all these years later, was that my impulse?

“One of the historical theories about handshakes between men is that the gesture was a way to ensure safety,” says Dr. Michael M. Crocker, founder and director of the Sexuality, Attachment & Trauma Project in New York City. “The handshake would prove that both parties were not holding a weapon.”

It’s a good story, but I’m not sure I really believe it. Am I reluctant to hug because I’m secretly afraid my close male friends will attack me with a broadsword? Does my subconscious think I’m a knight?

yI have been, in the distant past, so disconnected from myself that I am surprised when I am flooded with emotions like self-loathing or suffocating melancholy. This estrangement has led me, at times, to think I’m not an emotional guy. But I am emotional — I am rubber ducky bobbing in a sloshing bathtub of my own emotions. I want to be held and to hold, desperately.

I have opened up and sobbed during group therapy. I have hugged men after AA meetings, especially in those first few months when I felt split open, and my nerves were like keys jangling on a ring. I struggle to share my feelings with my girlfriend, but I ultimately do share them: I am angry, I am scared, I am so unbelievably happy you’re in my life.

And yet, sometimes I step into the bear trap of old habits, of punishing negative self-talk. I say awful things to myself: I’m not worth being loved, I’m a failure, I’m weak. And then there’s this thought: If I hug him, my friend, what if it feels so good I don’t want to let go?

These make-believe brutes were the only masculinity blueprint society provided. Item number one: Never touch another man unless you are going to kung-fu chop him.

According to Crocker, an aversion to hugging comes down to men being fearful, consciously or not, of how others might perceive them. “My experience has been that the fear of such affection is based on others questioning their sexuality,” he says. “In their minds, affection between cis-gendered men is correlated with being bisexual or gay.”

I grew up during a time when the word “gay” was used by boys to describe gentleness, compassion, affection, and anything “girly.”

“Gay” wasn’t to my heterosexual ears so much about sexuality as it was an insult and a warning, a way to bring boys who showed softness or sensitivity to heel. Being told “that’s gay” stung, a small exile. I yearned to be one of the guys, and I feared being seen as different and shunned, for something as simple as loving Les Miserables for its triumphant spectacle of sloppy feelings told in songs about requited love, the love of parents, and the love of comrades.

I loved my friends; I desperately wanted their approval and to process the awful, wonderful, liminal space between being a child and an adult, but I could never tell them “I love you.” That’s what you say to girlfriends and wives. Parents, when forced. And I certainly wouldn’t hug them. Instead, I’d punch them, good and hard on the shoulderand leave a heart-shaped bruise.

My dad hugged me, and I worried he’d never let go. I would have spontaneously combusted if any of my friends had seen him wrap his arms around me and kiss my forehead as if, by magic, it would turn me back into a 5-year-old hugging machine.

And I certainly wouldn’t hug my friends. No. Instead, I’d punch them, good and hard, in their arm and leave a heart-shaped bruise.

But everywhere else I looked, the message was clear: Never touch another man unless you are going to kung-fu chop him, like Chuck Norris.

There are all sorts of material benefits to embracing a friend or family member. Hugging triggers brain-soothing hormones like oxytocin, dopamine, and serotonin. A 2014 Carnegie Mellon study of 400 adults suggests that hugging can reduce stress and sickness. There are psychological benefits, too. Hugging can reinforce social bonds and relieve stress.

During the COVID lockdowns, I read renowned therapist Virginia Satir’s quote that people need four hugs a day for survival, eight for maintenance, and 12 for growth. Even then, trapped in my apartment, that sounded excessive.

I also admit I suffer from Ironic Bro Syndrome. I have referred to my close male friendships as ‘bromances,’ a word that simultaneously accepts and dismisses intimate male friendships.

The traditional rules of masculinity clearly state that men can only show each other affection under the cover of alcohol and big-screen TVs. This scenario is the birthplace of “I love you, man,” the ancient cry of cishet male drunks yearning to express their emotions in a safe place. I have been that dude, unhappy, shitfaced, overflowing with “I love you, mans.”

Modern masculinity is slowly normalizing male affection but society still “shames emotional vulnerability and platonic intimacy between men.”

“We all have a desire or need to reach to others for connection and care,” says Daniel Cook, LMHC, Executive Clinical Director of Embodied Mind Mental Health. “I would even say we are biologically wired for it, we are pack animals, after all.”

Modern masculinity is slowly normalizing male affection, but according to Cook, society still “shames emotional vulnerability and platonic intimacy between men.” Men, he continues, are not generally taught how to connect to other men, which is why their romantic partners often bear the full brunt of their emotional needs. That can strain relationships, and in some cases, push men toward self-destructive habits in an effort to self-soothe.

A hug isn’t a cure for loneliness and anxiety, but it helps.

I’m 49 years old. My wires get crossed all the time, too. My head says, “hug” but my hands say “No! Shake hands! Don’t be vulnerable!”

Cook understands my impulse and deals with it frequently in his practice. But he’s also seeing something else: men who are more open to emotional work and a new generation more unafraid to express vulnerability.

“I’m encouraged by the amount of men I see finding their way to therapy and yearning to be in real relationships with themselves and eventually each other,” says Cook. “I see a shift in the younger generation of boys who seem to be finding their way with each other. I think in part to the work this generation of fathers is doing.”

I see a shift in the younger generation of boys who seem to be finding their way with each other. I think in part to the work this generation of fathers is doing.

The friend I should have immediately hugged outside that diner is a father. By example, he’s teaching his boys to hug their friends without thinking. I hope most of all that I’m in the minority in my aversion to embracing.

I reached out to some other friends about their hug habits. There was a time I would have suffered in silence, but I wanted to prove to myself that I knew how to climb out of dark holes. The best way to understand how you’re feeling is to ask others how they’re feeling.

I relate to Dan, 54: “I am not a hugger. I’m so not a hugger that it’s a joke with my friends and family how much of a non-hugger I am.”

Dan thinks people should hug more, though. “No one shot up a school or their workplace because they were hugged too much or shown too much kindness.”

Brendan, 40, started going to punk shows at 13 in New England. This was a sweaty, loud scene. Basements. Screaming. Tattoos. But the show would stop if a fight broke out in the mosh pit. “So, you would have to hug it out if someone knocked you over,” he says. “Such a perfect outlet for teenage aggression.”

He continues, “There were teens who were afraid of being gay but there were older kids with pierced noses, who would be like, ‘If there’s nothing wrong with being punk, why would there be something wrong with being gay?’ ”

My old man served in the Army; he’s buried in Fort Sam Houston outside of San Antonio. So I wasn’t surprised when Rob, 55, enthusiastically endorsed hugging. He works for the U.S. Marine Corps, where he served from 1986 to 2006, and he hugs his fellow servicemen and women whenever he sees them.

— Getty Images

“The men and women I served with became my family, we all looked out for one another,” he said. “I hesitate to call it a ‘brotherhood’ because halfway through my service, the influx of women into seagoing commands occurred, and I see the women I served with to be part of this special bond as well, it is indeed a family.”

Displays of affection between men are, of course, largely cultural, too. John, 49, grew up in Greek culture, where its normal for men give each other the kiss hello on each cheek. But, he says, “the only time I have ever hugged any of my American-born friends was at funerals, unfortunately.”

I found comfort in these stories, even if I sometimes felt less evolved. I also felt less alone, and there’s a lesson for men there. Talk to your friends. They’ll surprise you. And then, maybe, you’ll surprise yourself. The next time I catch up with any of these friends, I will give them The Sasquatch.

Was the fist bump born in the boxing ring? Did handshakes evolve from knights proving they weren’t a threat by opening their hands?

Here’s a new story. I made it up, but feel free to tell it and get it circulating. It goes like this: hugs between people who identify as male can be traced back hundreds of years to shining knights in their armor meeting on the road. One knight would open his arms, and the other would do so too, and they’d hug as a greeting, their steel breastplates crashing against each other, and their gauntlets clanking on metal backplates.

This is not a historically accurate story, but I want it to be true: Once upon a time, men hugged, now you should too.